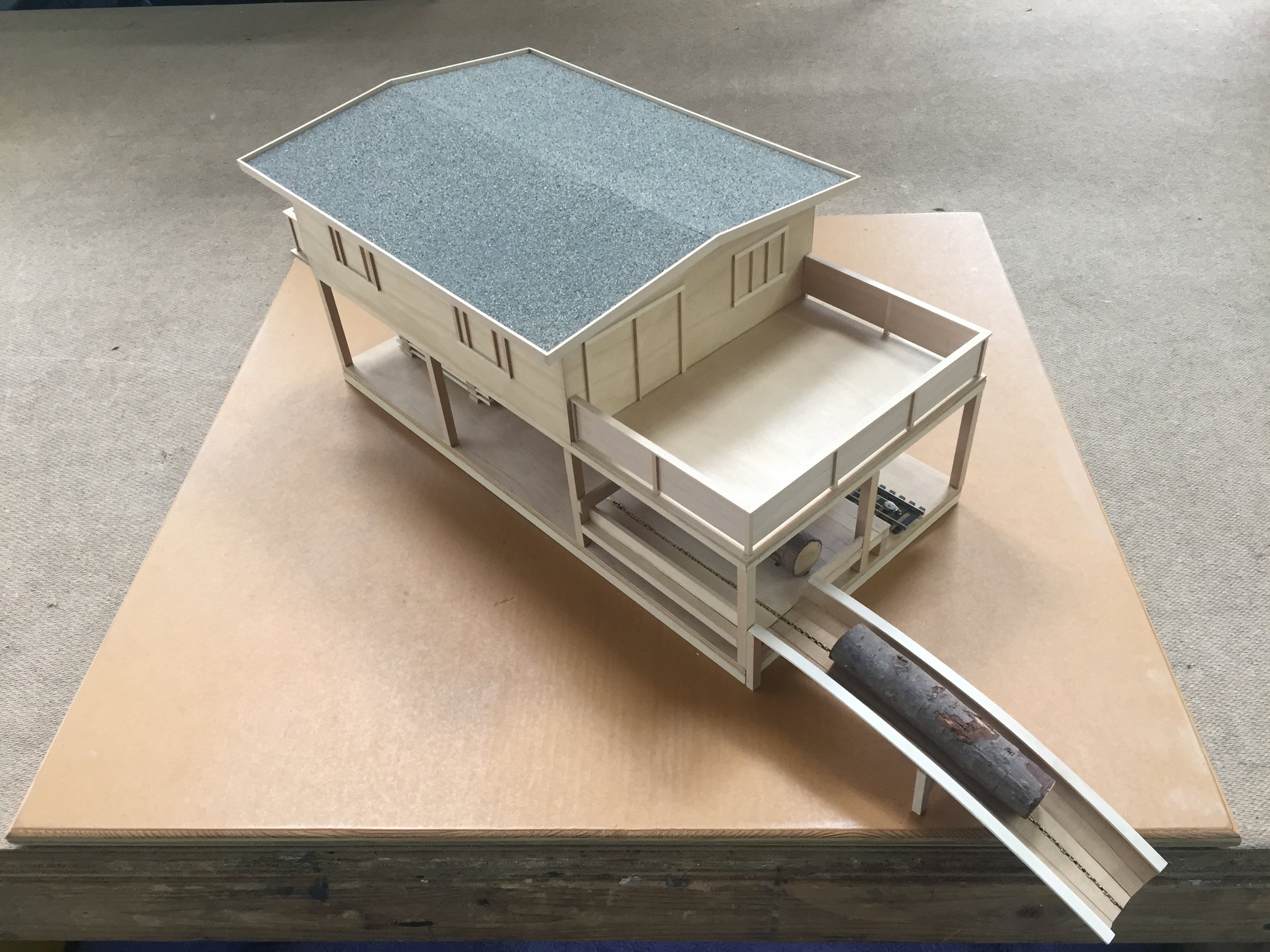

Project for False Creek

(Vancouver Special Sawmill)

mixed media

12” x 24” x 24”

2012

The rich industrial history of False Creek is here recalled in the presence of a rudimentary working sawmill on its shoreline, drawing fir logs up a jack-chain to the mill, cut into 2x4s for the stud-framing of a two-story Vancouver Special built around it. The work highlights certain civic tensions that continue to exist in Vancouver–the steady loss of practical and pragmatic manufacturing jobs, replaced by ever-increasing service industries; and explosive high-density condo development and real-estate speculation stripping affordable housing from the city. These dichotomies form the core of Project for False Creek.

False Creek is an inlet separating downtown Vancouver from residential districts to the south and east. From the late 19th century to the latter part of the 20th, its shoreline accommodated a range of light and heavy industries, mostly providing resource-extraction equipment for the province’s three major economies: fishing, logging and mining. Sawmills, shipyards, foundries, forges, chain and wire-cable companies, machine shops, cooperages and the like crowded the waterfront. Granville island, a reclaimed sandbar, became its industrial centre. Main Street, once a causeway carrying a flume from Trout Lake to the lumber mills of Gastown, supported a Victorian birdcage public market near the present location of Science World. East of Main, the mudflat extending to Clark Drive was filled in to provide for rail shunting yards and the city’s major train station, the passenger terminus of the transcontinental railroads.

The Vancouver Special, a type of affordable single-family detached domestic housing developed in Vancouver BC during the 1960s, was developer-designed to maximize the allowable square-footage volume on a given lot size, within permissible zoning-regulations, building-codes, setbacks and height restrictions. Typical houses in this style were built on grade on a concrete slab, between 1500 and 2500 square feet, with a shallow-pitched tar-and-gravel roof, often with a flat-roofed integrated rear carport serving as a porch deck. Shallow full-width balconies and stone or brick facades are typical, with upstairs living spaces and downstairs bedrooms, easily converted to secondary suites. The type, hugely popular with contractors due to its very profitable mass-production format, was in the beginning strongly supported by a developer-friendly city council. But its boxy shape with slight variation and endless repetition came to be regarded as a blighted failure of the architectural imagination, and in the late 80s zoning by-laws were changed to discourage further building.

But early in the new century the fundamental form’s plastic potential and spatial simplicity attracted a number of creative younger architects, who devised thoughtful renovation plans for existing Specials, based on internal reorganizations influenced by mid-century modernism and loft-style artist’s live-work spaces. These initiatives were not at first encouraged by city hall, which would rather have seen their now-embarrassing proliferation vanish; but persistent home-owners, architects and builders have been able to produce functional, attractive and award-winning re-conceptualizations of the type.